1900

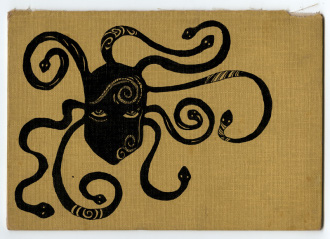

Painted postcard, marionette show, probably Myanmar

1900 Sardar patel Passed the District Pleader's Examination; practices in Godhra; contracts bubonic plague from a court official whom he nursed during an epidemic in Godhra

the plague in phalke's journey

Lord Curzon visits Ajanta Caves, he has just started his tenure as Governor General, his visit will influence him to pass a law decreeing a preservation of monuments.

Photographic transfer process introduced in India soon after 1900 by Dada Saheb Phalke. He set up his own studio in Malvali that worked for the Ravi Varma Press but also for other printers in the area. colour transfer of pictures in conjunction with photography. ( seems like this is a wrong date?)

Sundials tell "sun time". Clocks and watches tell "clock time". Neither kind of time is

intrinsically "better" than the other - they are both useful and interesting for their separate

purposes.

"Sun time" is anchored around the idea that when the sun reaches its highest point (when

it crosses the meridian), it is noon and, next day, when the sun again crosses the

meridian, it will be noon again. The time which has elapsed between successive noons is

sometimes more and sometimes less than 24 hours of clock time. In the middle months of

the year, the length of the day is quite close to 24 hours, but around 15 September the

days are only some 23 hours, 59 minutes and 40 seconds long while around Christmas,

the days are 24 hours and 20 seconds long.

"Clock time" is anchored around the idea that each day is exactly 24 hours long. This is

not actually true, but it is obviously much more convenient to have a "mean sun" which

takes exactly 24 hours for each day, since it means that mechanical clocks and watches,

and, more recently, electronic ones can be made to measure these exactly equal time

intervals.

The seasonal correction is known as the "equation of time" and must obviously be taken

into account if we want our sundial to be exact to the minute.

If the gnomon (the shadow casting object) is not an edge but a point (e.g., a hole in a

plate), the shadow (or spot of light) will trace out a curve during the course of a day. If

the shadow is cast on a plane surface, this curve will (usually) be a hyperbola, since the

circle of the sun's motion together with the gnomon point define a cone, and a plane

intersects a cone in a conic section (hyperbola, parabola, ellipse, or circle). At the spring

and fall equinox, the cone degenerates to a plane and the hyperbola to a line. With a

different hyperbola for each day, hour marks can be put on each hyperbola which include

any necessary corrections. Unfortunately, each hyperbola corresponds to two different

days, one in the first half and one in the second half of the year, and these two days will

require different corrections. A convenient compromise is to draw the line for the "mean

time" and add a curve showing the exact position of the shadow points at noon during the

course of the year. This curve will take the form of a figure eight and is known as an

"analemma". By comparing the analemma to the mean noon line, the amount of

correction to be applied generally on that day can be determined. At the equinox, we

found that the solar day is closer to the sidereal day than average, that is, it is shorter, so

the sundial is running fast. That means in fall and spring the correct time will be earlier

than the shadow indicates, by an amount given by the curve. In summer and winter the

correct time will be later than indicated.

http://www.sundials.co.uk/newdials.htm

The sundials at Jaipur, India

http://www.photonetal.com/stock.indiantms

also lots of information about the sundial and Jaipur Observatory at

http://www.jiva.org/observe/jaipur/life3.html

http://www.sundials.co.uk/mottoes.htm

(Taken from the net).

It is the year 1900.

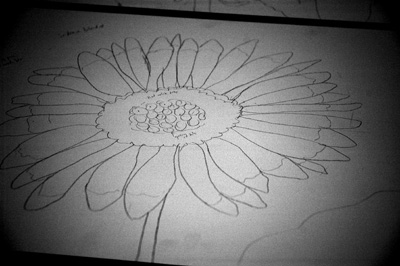

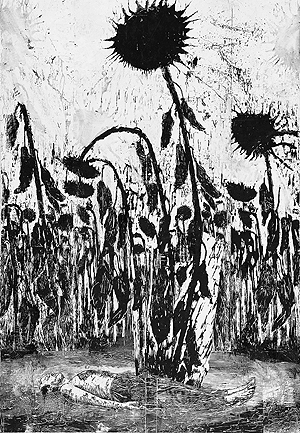

The shadow of the sunflower plant cast a lazy hyperbola on the damp red earth as the day

progressed. Karna observed this everyday by fixing thin twigs every hour at the exact

point of the end of the shadow. He had never believed that sunflowers were really true in

their adoration of the sun but this simple exercise convinced him more than books or

anecdote would. He had the mind of an investigator and a never say die attitude which

wormed its way into his mind, his instinct, his gut, his spleen, the very heart of his being.

Having just moved to Baroda with its beautiful public parks and surrounding farmlands,

observing nature had become one of his obsessions. An inner darkness haunted him and

he found shadows fascinating. He wondered if he could devise a way of reading a

shadow. Like dreams, he was convinced, shadows too had meaning. The darker side of

the psyche perhaps or a constant warning that as with time things were always in flux but

came round again to the same beginning and then the same end – the eternal cyclical

construct of life. Light and dark, the corporeal and the shadow lived like ghosts in a

certain twilight zone of his mind.

Baroda, home to the conquering Marathas now was ruled by Maharaja Sayajirao. A

visionary and polymath and educationist with a deep humanistic streak, his policies

fascinated Karna. The scientific bent of mind that he, Karna, had inherited from centuries

of random genetic distillation was coupled with a powerful drive to create and express

himself. His sunflower experiment he felt would interest the erstwhile king but he needed

another dimension to gain entry into the royal darbar. Karna was a polymath too and a

master in many crafts and arts and was receiving excellent guidance and inspiration from

his teachers at the Baroda university (established by none other than M Sayajirao).

Karna lived in a small room by the river. The room was cluttered with the paraphernalia

of someone who was obsessed with making things. There were carpenters tools, old iron

parts that looked like they had seen the last of their days, gears and cogs and metal drums

and crushed bicycle wheels and springs and even a collection of old cameras. There were

shapeless lumps of glass, glass beads and marbles of every hue and colour. Amidst all

this clutter as we might choose to see it were blossoming forth forms of complex

mechanical objects that looked like prehistoric robots. Cranked gear wheels made up the

faces, they had limbs that moved when a key turned a spring in the back but the exact

purpose of these inventions elude us until we see that each object is meticulously placed

somewhere in the room where they receive varying light from the sun pouring in through

the window. The reality of his inventions for him was their shadow. The spaces through

that were asymmetric blobs of light, the distorted gear wheel that lenghthened and

shortened as the sun transited the sky. His knowledge of photography and experiments

with the light and the dark and his faithful old camera were his tools of the moment.

Each of these momentous shadow images was captured, neatly labeled and stored in a

box by his bed which was a mattress on the floor. But soon he had to learn some craft that

would bring in some money to pay for his experiments and living expenses. One of his

professors at college mentioned to him that there was a visiting anthropologist from

England who was doing studies of the people of urban cities. Karna had just recently

learned of the Magic Lantern shows of James Edwards. The photographs intrigued him

and he specially liked the one of the mother and child running from the camera, as it were

running from their own shadow.

The anthropologist required a photographer to accompany him and document his

findings. Karna jumped at the opportunity. In the library he had seen a number of

illustrated books filled with photographs of far away lands and exotic and strange people.

There were also books about princes of India, portraits that had been actually coloured in.

But what fascinated him most were the black and white images which seemed to him the

absolute perfection of resolution of light on object. In darkness and in light.

One of the books had an image of an Indian prince sitting on his throne. At his feet lay a

tiger skin and on the tiger skin was placed a sundial. There was a north facing window to

the right of the image and the light through the window on the gnome cast a rippled

shadow on the stripes of the tiger skin. Was this some metaphor of the kings mortality,

did it locate the photograph or the incident. The king’s figure too cast a shadow. It was

longer than that cast by the largish sundial. Was this an intentional symbolism of the

king’s invincibility, or was the king a gadget freak and the image a simple coincidence.

He examined all the shadows closely almost losing sight of the photograph and then the

idea hit him.

He would make a living sunflower sundial for the king – a lover of nature, science and

investigation. He would place him in the midst of the Italian fountain in the palace

grounds surrounded by the manicured, topiaried gardens that surrounded it. He would

then photograph him. For, it had suddenly struck him that we are all gnomes of a sundial.

Being three dimensional, a part of us, in the open, would always be North facing. That

problem surmounted, he knew enough about sundials to know that the orientation of the

gnome needed to be at an angle equal to the latitude of the place he was at. How do I get

the king to remain in a slanted position, he pondered. Several experiments followed of

finely carpentered king-gnome bases that would precariously bear the weight and

dimensions of the king. He wanted the truest, slanted image of the king looking straight

into the camera while the sunflower sundial (with the angled sunflower gnome) in front

of him while the fountains played merrily in the air casting rainbow colours that would

resolve themselves as arbitrary shades of grey and black on his image. All a shadowland.

He would then take many photos of the king turned this way and that and then develop

them and study the shadow formations closely.

This study would let him make meaning of the king’s substance, his mortality, his

aspirations, his inner self and he could then tempt the king with his findings and have a

more private and intimate audience with the king. Voila! He now had his plan. But these

are his mental machinations as he starts to make progress with the project of the

anthropologist. His brief is to walk the streets of Baroda looking for both the typical and

the atypical face. What does such a project mean he asked himself. How does one

remove a subjectivity from such an endeavor? He starts to roam the streets. His camera is

bulky so he has sometimes to set it up in one place and wait for the chance passerby

whom he can lure into his world of trapping light and shade. The curious stop and look

but many are scared of this man and his contraption. He finds himself having to look at

faces, body types and the living being rather than the shadow. He starts to notice eyes. He

stares hard into the eyes of those who pass by often imagining reflections of himself in

those eyes. He starts to get sucked into those very beings. What would the king’s eyes be

like? How would they suck him in, he wonders. But, he has to stop his day dreaming and

get on with his assignment. He starts to take photographs of people quite arbitrarily. After

all there is an arbitrariness in how we come about to be what we are and look how we

look. Only the shadow is not arbitrary. It is a consequence and it is true.

Eyes, shadows, light, dark, sundials, kings and this potpourri of metaphorical allusions

dominate his life. The anthropologist is at first puzzled by the photographs and finds that

Karna’s cityscape is made up of a multiplicity of ideals. He has no locus and the typical

eludes him. They have long discussions about what it means to sift and sort from the

menagerie we live in – he particularly alludes to the photographs that Karna has taken of

monkeys in the zoo and interspersed with photographs of people. The project seems to be

going out of control. Karna cannot be the true zookeeper of the human zoo. He is

floundering in the eyes and shadows of his subjects. His inability to control such an

experiment and make a definition of form and image of his subjects perplexes both his

teacher and the anthropologist. They decide that he perhaps is not the right person for the

task at hand so he is jobless and perhaps relieved that he can get on with his sundial

project and his mission to befriend the king. His life seems to be lived in a non reality of

illusion and a self created fiction.

It is a market day in the walled city of Baroda. Karna and camera wander aimlessly

through the narrow streets overrun by vendors selling their plunder from people’s homes.

The streets are noisy with the cries of hawkers and vendors and the heated bargaining that

goes on. As he continues to walk he suddenly notices he has entered an oasis of silence.

There is a crowd of people standing in a circle. They seem to be intently focused. He is

curious for once. He pushes his way through to see what they are all looking at. At the

center of the circle he sees a young woman sitting cross legged. She is dressed in a saree

with her head covered and there is not much he can see of her face. She is playing the

snake charmers flute. The sun is at its eight am position and she casts a strange shadow

on the ground. In front of her there is a basket with a cobra. The cobra is swaying to the

movement of the flute. In contrast to the still shadow of the woman the snake’s extended

shadow glides sensuously away and towards the woman’s shadow. He is enthralled. He

needs to see her eyes but the show ends abruptly. People throw money into her bowl and

she starts to pack up her snake, basket and flute. Never once does the veil fall from her

head. He can’t forget the sinuous movement of the snake which seems to adore her

shadow-body. He follows her through the streets until they arrive at a small house near

the edge of the market. As she enters her door he calls out in greeting. She turns in

surprise and her saree falls off her head. Her eyes are the most piercing eyes he has ever

seen. They are as dark as a moonless night and no light seems to enter them. He can’t see

her irises. But they reflect him clearly. He feels that she does not see him but is simply

mirroring him, deflecting him. An agony perhaps of years lived on the fringes of life

condemned to a life of a shadowy entwinement with a snake. A deep feeling like he has

never felt before stirs within him and he moves towards her as though drawn by some

strange force. He needs those eyes to let him in. He is the charmed and the charmer too.

He is not content with being a reflection or not even a shadow. His feeling of

omnipotence over the shadow world does not extend to his own shadow and the fear of

being that to her once she stops reflecting him compels him yet more towards her. She

retreats through the door and it closes. The sun is now behind him and for the first time

he notices his shadow on her door.

We photograph things to drive them out of our minds. My stories are my way of shutting my ears. Franz Kafka

A few days pass of him living in a dreamy reverie. Flashes of her, of eyes, shadows,

reflections punctuate this time. He needs now to get on with his king-sundial experiment.

He starts to grow sunflowers in a small patch of ground by the river behind his house. He

uses support sticks to trace out various inclinations for the plant. Days go by. The plants

are growing. He is completely absorbed. He does not notice that the days are sometimes

cloudier than normal. It is the sign of the impending monsoons. He is woken up early one

morning to the sounds of thunder and intense flashes of lightening that send strange

momentary shadows flickering around his room. He rushes out to his sunflowers and

finds that they are bent over in the torrential rain and winds. He maniacally tries to

restore them to their positions but it is all in vain. The rains continue to lash the city. He

watches the river fill up slowly. The overcast skies leave no chance for shadows to

survive. He misses the sun. The circularity of night and day, of shadow and noon-day no

shadow cease to exist and for him with that ceases to exist the very core of his meaning

of life.

He is oblivious now even to the rising river. One day soon the waters start to enter his

house. At first slowly and then with no warning at all it has risen a few feet. His

mechanical contraptions are submerged. He is frantically trying to save whatever he can

but it is too late. The inexorable march of nature is consuming him. For him it is a

metaphor for a kind of dying. He wonders what he will be reborn as. He watches

helplessly as the water takes with it his precious box of photographs. The box breaks into

bits and the photographs float around the room and are sucked out into the raging torrent

of the river. His room is now almost half filled with water and is continuing to rise. His

instincts start to take over as he sees his life’s work ebb away from him. He stumbles

through the water and is forced through the door by the current. It is the tide of life – one

last photograph floats after him. It is an image of the maharaja with a sundial.

Leela Mayor, Baroda, 27th August 2006

The Railway Panorama [1] The Panoramas of the late nineteenth century, in Paris particularly, created special effects: Charles Castellani's Le Tout Paris had the Opera and areas around the Opera, and all the dignitaries of the city.. the spectator moved around the Panorama, experiencing being there In 1892 Then there were recreations of historical events- witnessing the sinking of ships, for instance, in which spectators stood on a deck, which moved and a background was created of the sinking, and of surrounding enemy ships..sounds of gunfire, cannons and a chorus singing the Mareillase After the arrival of cinema, spectators got to sit before on a 'ship' before projections of moving photographic images of different coasts, rather than a rolling canvas, as was used before.. [2]