Hero’s Journey

The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) is the seminal work of comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell. In this text Campbell discusses his theory of the journey of the archetypal hero found in world mythologies and religions.

Contents

Overview

Campbell used the work of early 20th century theorists to develop his model of the hero (see also: structuralism), including Freud (particularly the Oedipus complex), Carl Jung (archetypal figures and the collective unconscious), and Arnold Van Gennep (the three stages of The Rites of Passage, translated by Campbell into Departure, Separation, and Return). Campbell also looked to the work of ethnographers James Frazer and Franz Boas and psychologist Otto Rank.

Campbell called this journey of the hero, The Monomyth [1]. As a a noted scholar of James Joyce (in 1944 he authored the text (with Henry Morton Robinson), A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake [2]), Campbell borrowed this term from Joyce's Finnegans Wake. In addition, Joyce's Ulysses was also highly influential in the structuring of The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

The Princeton University Press published all editions of this text. Originally issued in 1949 , The Hero with a Thousand Faces has been reprinted a number of times. Reprints issued after the release of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope in 1977 used the image of Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker on the cover [3]. The Commemorative Edition (published in 2004) has both a new introduction by Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Ph.D., as well as a new cover [4].

Quotes

Preface:

- "There are of course differences between the numerous mythologies and religions of mankind, but this is a book about similarities; and once they are understood the differences will be found to be much less great than is popularly (and politically) supposed. My hope is that a comparative elucidation may contribute to the perhaps not-quite desperate cause of those forces that are working in the present world for unification, not in the name of some ecclesiastical or political empire, but in the sense of human mutual understanding" (third edition, p. viii).

- "As we are told in the Vedas: 'Truth is one, the sages speak of it by many names,' " (third edition, p. viii).

Contents

Prologue: The Monomyth

- 1. Myth and Dream

- 2. Tragedy and Comedy

- 3. The Hero and the God

- 4. The World Navel

PART ONE: The Adventure of the Hero

Chapter I: Departure

- 1. The Call to Adventure

- 2. Refusal of the Call

- 3. Supernatural Aid

- 4. The Crossing of the First Threshold

- 5. The Belly of the Whale

Chapter II: Initiation

- 1. The Road of Trials

- 2. The Meeting with the Goddess

- 3. Woman as the Temptress

- 4. Atonement with the Father

- 5. Apotheosis

- 6. The Ultimate Boon

Chapter III: Return

- 1. Refusal of the Return

- 2. The Magic Flight

- 3. Rescue from Without

- 4. The Crossing of the Return Threshold

- 5. Master of the Two Worlds

- 6. Freedom to Live

Chapter IV: The Keys

PART TWO: The Cosmogonic Cycle

Chapter I: Emanations

- 1. From Psychology to Metaphysics

- 2. The Universal Round

- 3. Out of the Void -Space

- 4. Within Space -Life

- 5. The Breaking of the One into the Manifold

- 6. Folk Stories of Creation

Chapter II: The Virgin Birth

- 1. Mother Universe

- 2. Matrix of Destiny

- 3. Womb of Redemption

- 4. Folk Stories of Virgin Motherhood

Chapter III: Transformations of the Hero

- 1. The Primordial Hero and the Human

- 2. Childhood of the Human Hero

- 3. The Hero as Warrior

- 4. The Hero as Lover

- 5. The Hero as Emperor and as Tyrant

- 6. The Hero as World Redeemer

- 7. The Hero as Saint

- 8. Departure of the Hero

Chapter IV: Dissolutions

- 1. End of the Microcosm

- 2. End of the Macrocosm

Epilogue: Myth and Society

- 1. The Shapeshifter

- 2. The Function of Myth, Cult, and Meditation

- 3. The Hero Today

Influences

General

The Hero with a Thousand Faces has influenced a number of artists, musicians, poets, and filmmakers, including Bob Dylan and George Lucas. Mickey Hart, Bob Weir and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead had long noted Campbell's influence and agreed to participate in a seminar with him in 1986 entitled From Ritual to Rapture [5].

George Lucas and Star Wars

George Lucas's deliberate use of Campbell's theory of the monomyth in the making of the Star Wars movies is well-documented. In addition to the extensive 1987 discussion between Campbell and Bill Moyers broadcast on PBS as The Power of Myth (filmed at Skywalker Ranch}, on Campbell's influence on the Star Wars films, Lucas, himself, gave an extensive interview for the biography Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind (Larsen and Larsen, 2002, pages 541-543) on this topic. In this interview, Lucas states that in the early 1970s after completing his early film, American Graffiti, "it came to me that there really was no modern use of mythology...so that's when I started doing more strenuous research on fairy tales, folklore and mythology, and I started reading Joe's books. Before that I hadn't read any of Joe's books.... It was very eerie because in reading The Hero with A Thousand Faces I began to realize that my first draft of Star Wars was following classical motifs"(p.541).

12 years after the making of The Power of Myth, Moyers and Lucas met again for the 1999 interview, the Mythology of Star Wars with George Lucas & Bill Moyers, to further discuss the impact of Campbell's work on Lucas' films [6]. In addition, the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution sponsored an exhibit during the late 1990s called Star Wars: The Magic of Myth which discussed the ways in which Campbell's work shaped the Star Wars films [7]. A companion guide of the same name was published in 1997.

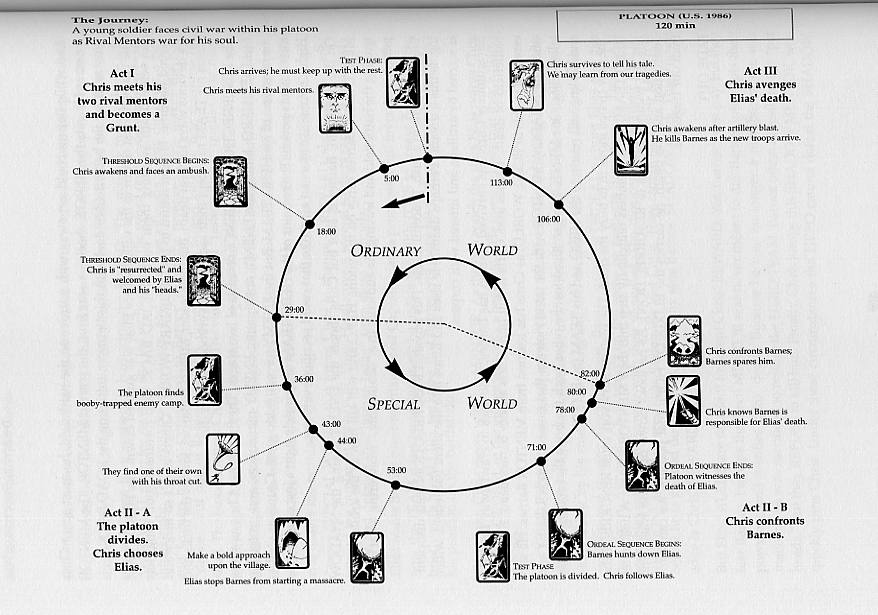

Chris Vogler, The Writer's Journey, and Hollywood films

Chris Vogler, a Hollywood film producer and writer, created a now-legendary 7-page company memo, A Practical Guide to The Hero With a Thousand Faces, based on Campbell's work which inspired films such as Disney's 1994 film, The Lion King. Vogler's memo was later developed into the late 1990s book, The Writer's Journey, which became the basis for a number of successful Hollywood films and is believed to have been used in the development of the Matrix series.

Criticism

- Clyde W. Ford (2000), was initially distressed by the opening lines of the prologue to The Hero with a Thousand Faces. He eventually returned to the text, in order to synthesize what was of value to him: "Several months passed before I mustered the courage to challenge Campbell again...I was rewarded for my persistence. Campbell's shortsightedness about Africa could not obliterate his immense contributions to mythology, and his omission gave me an opportunity to explore African mythology in a novel and meaningful way," (p. 12).

- Marc Manganaro (1992), argues that Campbell's theories violate the expectations of poststructuralism: "Campbell's reading of mythology as text hardly aligns with post-structuralist notions of "world as text," as a realm of constantly shifting signifiers having no provable reference to a ground of signified meaning...on the contrary Campbell's trope of 'text'...functions as a shell that covers the true interior of the myth" (p. 159).

- Pearson and Pope (1981), claim that Campbell's model discounts the possibility of female heroes: "The great works on the hero--such as Joseph Campbell's The Hero With A Thousand Faces...all begin with the assumption that the hero is male" (p. vii).

- Novelists Kurt Vonnegut and David Brin have been openly critical of his theories.

- Novelist David Foster Wallace in the short story Another Pioneer (part of the collection, Oblivion, 2004) critiques Campbell's journey of the hero.

Trivia

- The hero's journey is parodied in two South Park episodes:

- 613:The Return of the Lord of the Rings to the Two Towers

- 614: The Death Camp of Tolerance (through the journey of Lemmiwinks)

References

- Cousineau, Phil and Stuart L. Brown (eds.). The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work. New World Library: 1st New World edition, 2003. ISBN 1577314042.

- Campbell, Joseph and Henry Morton Robinson. A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, 1944.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949.

- Ford, Clyde W. The Hero with an African Face. New York: Bantam, 2000.

- Henderson, Mary. Star Wars: The Magic of Myth. Companion volume to the exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. New York: Bantam, 1997.

- Larsen, Stephen and Robin Larsen. Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2002.

- Manganaro, Marc. Myth, Rhetoric, and the Voice of Authority: A Critique of Frazer, Eliot, Frye, and Campbell. New Haven: Yale, 1992.

- Moyers, Bill and Joseph Campbell. The Power of Myth. Anchor: Reissue edition, 1991. ISBN 0385418868

- Pearson, Carol and Katherine Pope. The Female Hero in American and British Literature. New York: R.R. Bowker, 1981.

- Vogler, Christopher. The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, second edition. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998.

External links

- The Archetype of the Hero's Journey from Web English Teacher

- Second edition from the Joseph Campbell Foundation.

- A Practical Guide to THE HERO WITH A THOUSAND FACES

- Joseph Campbell's Hero Journey at MonoMyth.org

- The Hero Cycle as seen in the Star Wars saga

- Starwars Origins - Joseph Cambell

no:Helten med ett Tusen Ansikt

The hero's journey : summary of the steps

This page summrarizes the brief explanations from every step of the Hero's Journey.

Departure

The Call to Adventure

The call to adventure is the point in a person's life when they are first given notice that everything is going to change, whether they know it or not.

Refusal of the Call

Often when the call is given, the future hero refuses to heed it. This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the person in his or her current circumstances.

Supernatural Aid

Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously, his or her guide and magical helper appears, or becomes known. The Crossing of the First Threshold This is the point where the person actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of his or her world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are not known.

The Belly of the Whale

The belly of the whale represents the final separation from the hero's known world and self. It is sometimes described as the person's lowest point, but it is actually the point when the person is between or transitioning between worlds and selves. The separation has been made, or is being made, or being fully recognized between the old world and old self and the potential for a new world/self. The experiences that will shape the new world and self will begin shortly, or may be beginning with this experience which is often symbolized by something dark, unknown and frightening. By entering this stage, the person shows their willingness to undergo a metamorphosis, to die to him or herself.

Inititation

The Road of Trials

The road of trials is a series of tests, tasks, or ordeals that the person must undergo to begin the transformation. Often the person fails one or more of these tests, which often occur in threes.

The Meeting with the Goddess

The meeting with the goddess represents the point in the adventure when the person experiences a love that has the power and significance of the all-powerful, all encompassing, unconditional love that a fortunate infant may experience with his or her mother. It is also known as the "hieros gamos", or sacred marriage, the union of opposites, and may take place entirely within the person. In other words, the person begins to see him or herself in a non-dualistic way. This is a very important step in the process and is often represented by the person finding the other person that he or she loves most completely. Although Campbell symbolizes this step as a meeting with a goddess, unconditional love and /or self unification does not have to be represented by a woman.

Woman as the Temptress

At one level, this step is about those temptations that may lead the hero to abandon or stray from his or her quest, which as with the Meeting with the Goddess does not necessarily have to be represented by a woman. For Campbell, however, this step is about the revulsion that the usually male hero may feel about his own fleshy/earthy nature, and the subsequent attachment or projection of that revulsion to women. Woman is a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life, since the hero-knight was often tempted by lust from his spiritual journey.

Atonement with the Father

In this step the person must confront and be initiated by whatever holds the ultimate power in his or her life. In many myths and stories this is the father, or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving in to this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity, it does not have to be a male; just someone or thing with incredible power. For the transformation to take place, the person as he or she has been must be "killed" so that the new self can come into being. Sometime this killing is literal, and the earthly journey for that character is either over or moves into a different realm.

Apotheosis

To apotheosize is to deify. When someone dies a physical death, or dies to the self to live in spirit, he or she moves beyond the pairs of opposites to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion and bliss. This is a god-like state; the person is in heaven and beyond all strife. A more mundane way of looking at this step is that it is a period of rest, peace and fulfillment before the hero begins the return.

The Ultimate Boon

The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is what the person went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare and purify the person for this step, since in many myths the boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a plant that supplies immortality, or the holy grail.

Return

Refusal of the Return

So why, when all has been achieved, the ambrosia has been drunk, and we have conversed with the gods, why come back to normal life with all its cares and woes?

The Magic Flight

Sometimes the hero must escape with the boon, if it is something that the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and dangerous returning from the journey as it was to go on it.

Rescue from Without

Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest, often times he or she must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to everyday life, especially if the person has been wounded or weakened by the experience. Or perhaps the person doesn't realize that it is time to return, that they can return, or that others need their boon. The Crossing of the Return Threshold The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world. This is usually extremely difficult.

Master of the Two Worlds

In myth, this step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds.

Freedom to Live

Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past.